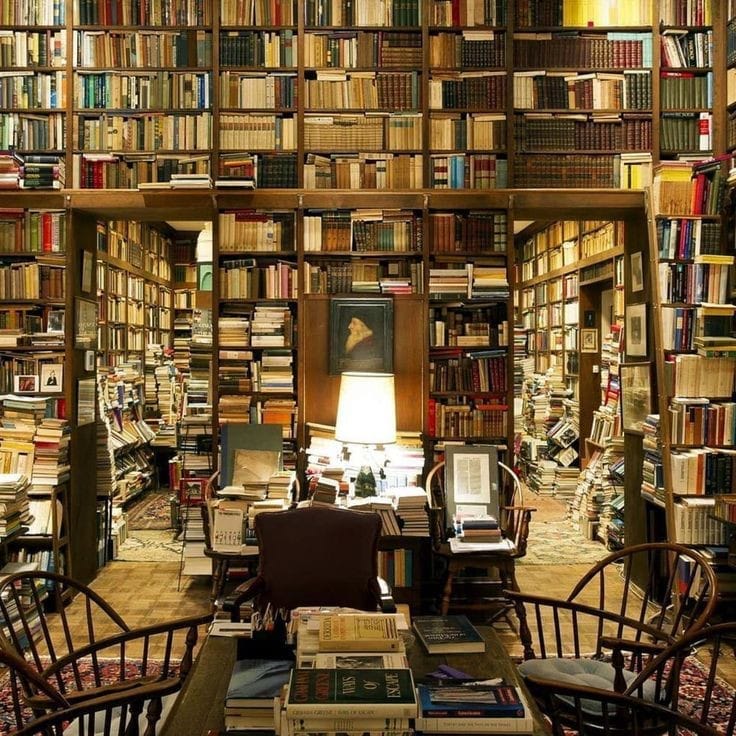

We approach books as sources of pleasure, of knowledge, seeking answers, seeking escape; but we also approach the book as an object, as a thing that has beauty and that we need only for pleasure, for possession. It is not something new, human beings have always sought to surround themselves with beauty, to preserve what they consider unique, beautiful, valuable. Keeping for yourself the most special things, wrapping yourself in collections of strange objects, objects whose main value is that, beauty. Books are beautiful objects, we cannot deny that, if we are also voracious readers, if we also have a thirst for knowledge that is better, but the book as a thing to collect is a reality, and it is beautiful.

Our personal libraries are an intimate view into our soul, a letter of introduction and a language more honest than any talk. They and we change, or so it should be, we improve over the years. Our collections speak of what we love and desire, Sontag said that “a library is an archive of longings”, and I believe they are also a collection of dreams. Books are also a weapon to heal ourselves, understand the real world, understand the loneliness or pain we carry.

“You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read. It was books that taught me that the things that tormented me most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, who had ever been alive.”

— James Baldwin, The Doom and Glory of Knowing Who You Are, Life Magazine, May 24, 1963.

Being in contact with certain books connects us to people and distant, mysterious places, and romantically, to our own world. When creating collections we create links because each book has a soul, I learned that personally during the time I worked in a used bookstore, surrounded by stories and lost feelings.

We generally speak of the beginning of this bibliomania in the Renaissance, the first large collections of books and scrolls, personal libraries that were consolidated like jewels and stored not only centuries of knowledge, but centuries of beauty. Many of us bibliophile readers are no different and seek to create small collections of books, stories, languages and ideas. Does this mean that we read every book we own? Of course not, but we possess them and there is a bond and a strong and valuable feeling in possessing the book we want, building our libraries and collections that become a reflection of our mind and spirit.

Now, there is a fundamental difference between literary collecting and mindless consumerism, and that difference lies in good taste.

I know, whatever I say I may be considered elitist, old-fashioned, unfair... but I will still say it: there are good books and books that are useless. Read tenaciously, create great libraries, we must have a conscience when selecting our books. Cultivating our mind is a revolutionary act but also one of incredible responsibility, whether it is to read or collect books.

There is an immense, universal connection between the books we read, those we collect, and the minds of those writers we admire as well as those they admired. When I decide to read and collect all of Dostoevsky's work, I am not only filling myself with his own wisdom but also with that which he absorbed from others, from those he admired and read. That is why it is essential to have high criteria when choosing our readings and those books that we will collect. Umberto Eco expresses it wonderfully:

“I have many experiences that are, I think, common to all who possess very many books (I now have around forty thousand volumes, between Milan and my other houses) and to all who consider a library not just a place to keep books one has already read but primarily a deposit for books to be read at some future date, when one feels the need to read them. It often happens that our eyes fall on some book we have not yet read, and we are filled with remorse. But then the day eventually comes when, in order to learn something about a certain topic, you decide finally to open one of the many unread books, only to realize that you already know it. What has happened? There is the mystical-biological explanation, whereby with the passing of time, and by dint of moving books, dusting them, then putting them back, by contact with our fingertips the essence of the book has gradually penetrated our mind. There is also the casual but continual scanning explanation: as time goes by, and you take up and then reorder various volumes, it is not the case that the book has never been glanced at; even by merely moving it you glanced at a few pages, one today, another the next month, and so on until you end up by reading most of it, if not in the usual linear way. But the true explanation is that between the moment when the book first came to us and the moment when we opened it, we have read other books in which there was something that was said by that first book, and so, at the end of this long intertextual journey, you realize that even that book you had not read was still part of your mental heritage and perhaps had influenced you profoundly.”1

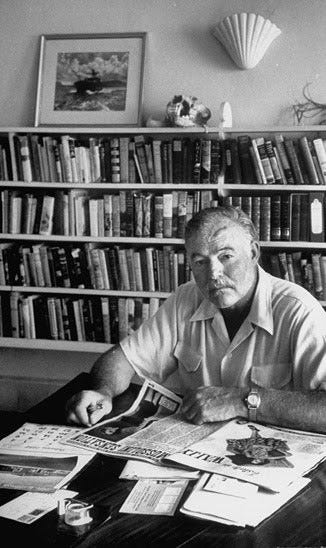

Collecting, in my opinion, has never been an arbitrary act. We surround ourselves with that which is beautiful, yes, but this beauty is linked to a notion of truth, wisdom and knowledge. Our personal libraries, regardless of size, are a construction of our learning, we do not read just for pleasure, we read because we need to know more, understand others, find ourselves in books. That necessary good taste is formed as we read the best of the best, the classics, those books that have marked different readers for centuries, books that were the favorites of other great writers and formed their criteria and style. It is that ancient chain that comes to us when we decide to select our readings thoughtfully. In the famous interview with Hemingway for the Paris Review by George Plimpton, when asked about his favorite books (a doubt that we readers genuinely always have regarding our favorite authors) the answer is monumental but makes it clear that it is in the classics where we must look for the truth and inspiration:

INTERVIEWER

Who would you say are your literary forebears—those you have learned the most from?

HEMINGWAY

Mark Twain, Flaubert, Stendhal, Bach, Turgenev, Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, Chekhov, Andrew Marvell, John Donne, Maupassant, the good Kipling, Thoreau, Captain Marryat, Shakespeare, Mozart, Quevedo, Dante, Virgil, Tintoretto, Hieronymus Bosch, Brueghel , Patinir, Goya, Giotto, Cézanne, Van Gogh, Gauguin, San Juan de la Cruz, Góngora—it would take a day to remember everyone. Then it would sound like though I were claiming an erudition I did not possess instead of trying to remember all the people who have been an influence on my life and work. This isn't an old dull question. It is a very good but a solemn question and requires an examination of conscience. I put in painters, or started to, because I learned as much from painters about how to write as from writers. You ask how this is done? It would take another day of explaining. I should think what one learns from composers and from the study of harmony and counterpoint would be obvious.

Finding ourselves in the words of an author, an author who in turn found himself in others, is a mystical process. Perhaps that is why many readers, including me, are obsessed with finding the list of favorite books of their favorite authors, reading what they loved and feeling more united.

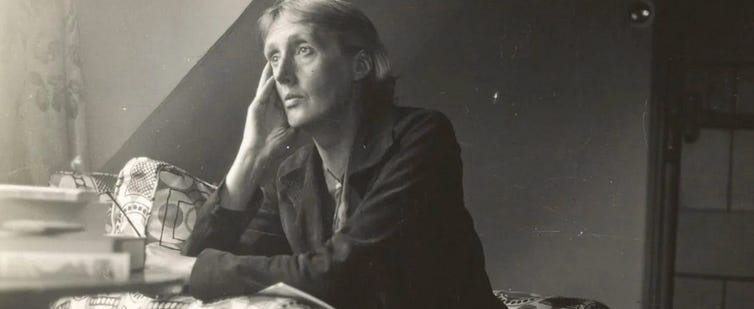

Virginia Woolf felt with Dostoevsky precisely this identification:

'Again and again we are thrown off the scent in following Dostoevsky's psychology; we constantly find ourselves wondering whether we recognize the feeling that he shows us, and we realize constantly and with a start of surprise that we have met it before in ourselves, or in some moment of intuition we have suspected it in others. But we have never spoken of it, and that is why we are surprised.'2

Collecting books in this way becomes an important part of how we see and understand ourselves, as well as a reflection of how we evolve. Every selection we make is fundamental, every book we acquire or why we do it. We read, collect and reread, the latter being another crucial factor, since visiting a book a second, third, thousandth time changes the way we understand it and the way the book, as an object, changes us. Collecting becomes not only a physical act but also a mental and emotional one.

“I’m re-reading pieces of things that have always been important to me, and I am amazed at my evaluations.” Susan Sontag

Collecting and reading books consciously introduces us to a special curatorial process. The decisions we make are thoughtful, the books we read, the recommendations we give, those we take home, everything is part of this. It is impossible, sadly, to read all the good books that exist, those that are still being written (I give a vote of confidence to some new writers) but our collections can become part of this battle against time.

“Reading Antigone,” Woolf wrote in her diary on October 29, 1934. “How powerful that spell is still—Greek. Thank heaven I learnt it young—an emotion different from any other.” Virginia Woolf on Sophocles.3

Reminder: marianaownroom will remain free, but if you want to support my writing and studies you can do it with Buy me a coffee

Eco, Umberto. On Literature. HarperVia, 2005.

Woolf, Virginia. Books and Portraits. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1978.

Woolf, Virginia. The Diary of Virginia Woolf, Vol. 3: 1925-30. Mariner Books Classics, 1981.

Thank you for this marvelous essay. I was particularly moved by Umberto Eco’s words on his library. I too have more books than I can sit down and read in my lifetime (I’m 78) but now I realize I have been reading them all along. Yesterday on impulse I read the first three pages of The Wealth of Nations. Will I read the remaining 897 pages? Probably not, and yet perhaps.

It also occurred to me that libraries are like gardens, and rarely survive the life of their builder. They are ephemeral yet beautiful and should be experienced as such.

Really good essay! I found Baldwin's quote particularly compelling. But I wonder about your conclusion about "good taste". It seems to me that authors whose works t have persisted over centuries and millennia -- Homer, Cervantes, Shakespeare, Melville -- have touched on things that universally resonate with the human spirit. But there are more temporal and quotidian books that are powerful or funny or poignant in their time, in their country, in their zeitgeist, that certainly won't last as long as Moby Dick or Don Quixote. For myself, I know that many of these books aren't of the greatest value, but they still nourish something in my spirit. I think one sometimes needs a little chocolate along with his/her bread.